non-fiction

publisher:

Gildendale

Release year:

2022

«Despite the new sources, Sæther repeats the old vulgarity.»

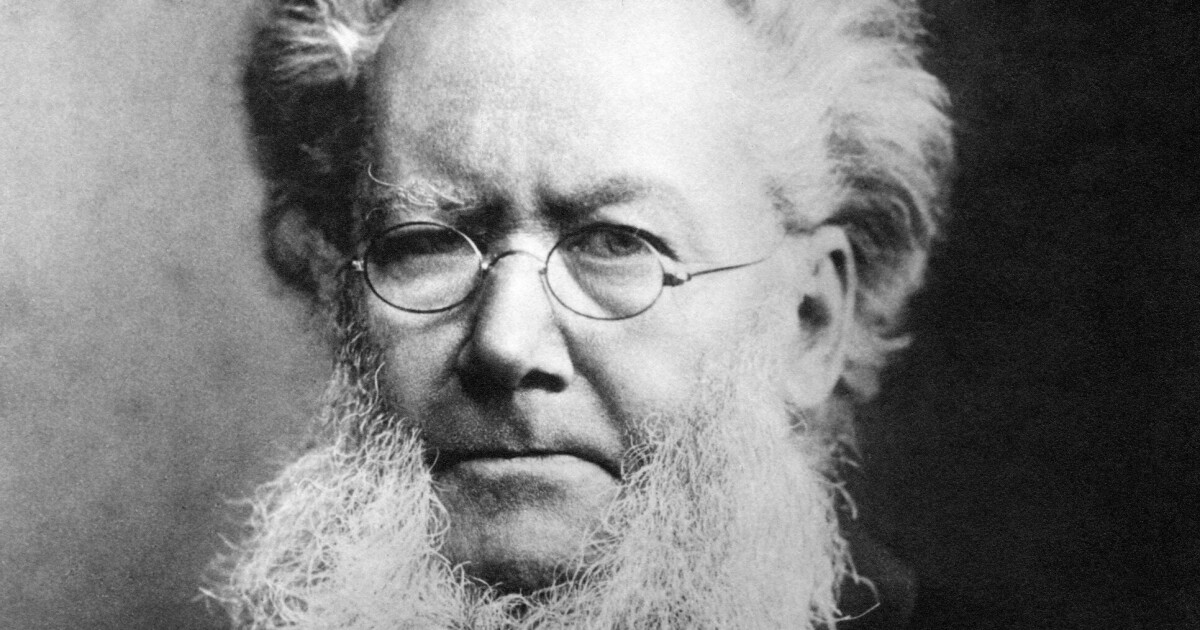

Let’s say right away that most people would agree that Ibsen’s affair with young women was active and inspiring. It is still debated over the extent to which they left their mark in his latest dramas as “Hoda Gabler”. However, there is no doubt that the focus today is first and foremost on the marital crises and social scandals created by his romantic relationships.

Not least because of Astrid Satheer’s work. She is a former director of the Ibsen Studies Center and has published an autobiography of the critically acclaimed playwright’s wife, Susanna. Mrs. Ibsen. Nor did men’s cinemas ignore the price the wife paid for Ibsen’s search for inspiration – in the form of humiliation, jealousy, gossip and long stays abroad.

However, the four young women who fell in love with the eldest Ibsen from 1889 to 1899 still shrouded in something mysterious. Although they lived long lives, and had careers as artists, writers, feminists, and intellectuals, cinemas were more interested in the brief periods that Ibsen lived in love with them. Unfortunately, Sæther’s book about them is also marked by them.

One of four: Norwegian pianist and educator Heldor Andersen became well acquainted with Ibsen. Photo: Gildendale

Show more

Ibsen’s eyes

This is particularly the case in the section on Austrian pianist Emily Bardach and Swedish dancer and composer Rosa von Wenghof. But also in the portraits of German painter and feminist activist Helen Raff and Norwegian pianist and teacher Heldor Andersen, Sather manages for a short time to free himself from his relationship with Ibsen and evaluate it with a new eye – freed from Ibsen’s earlier research. Approximately 60 of the 62 pages Sæther spends on Bardach is about the six months that the love affair lasted.

Examples of this brutal focus on Ibsen are unfortunately many. The most obvious is the title “In the Shadow of Ibsen”. How can a book be published in 2022 about four women and independent artists with this paternal title? At first, Sæther writes aggressively that “women must be highlighted”, but the same introduction opens and ends by placing them in the shadow of the genius and world spirit of Skien.

The IBSEN Relationship: German Painter and Feminist Helen Raff. Photo: Gildendale

Show more

Before we get a word out about their lives and work, she writes that “the encounters with Ibsen were groundbreaking and fateful for women.” It shouldn’t be underestimated that we had such a good time at my house last week doing one and the other “In the Shadow of Ibsen”.

Kisses and caresses

For those of us who are not from Ibsen cinemas, it is not easy to understand how the lives of others can be described almost exclusively in light of their brief and passionate relationship with a writer in the 1960s and 1970s. True, we know that he showered them with kisses and caresses when they were alone. Satheer also suggests that there may have been talk of sexual positions, i.e. what she gently calls “stress-charged prepositions and touches”. However, it is difficult to understand why her attempts to advance women ended with the release of Evo de Figueiredo’s famous words: “Women were a breeze in his life, while he was a storm in theirs.”

Rather than follow the sources and also include the sources you mention, but are to some extent used in your presentation, Sæther paints very traditional and sometimes tendentious pictures. Time and time again, Sather claims that the fate of their lives was marked by a brief courtship in summer, or that autumn with Ibsen shaped their lives – while they were episodes in his life. In several places, Sæther lives on in submission and credits them with a lack of “world spirit” and a pair that is not supported by quotations in the notes.

Young: Austrian pianist Emily Bardach was 18 when she met 61-year-old Ibsen. Photo: Gildendale

Show more

in exile

I was especially attached to the mention of Bardash – the “Princess of Orange”, as the cinema calls her. She was born in Vienna in 1862, where her father settled after leaving the Limberg Jewish Cultural Center. Despite the anti-Semitism, the father established himself as a merchant, and the daughter spent some time throughout Europe. She eventually settled in Switzerland because the country was neutral during World War II. This may also have been the reason why she did not fall victim to the persecution of Jews, but she died in Bern in 1955, at the age of 93.

Here and there we get a glimpse into Bardash’s life with support in her letter to George Brandes and newspaper articles about her relationship with Ibsen. The letters we get to know give a picture of her life in exile, but they are used to some extent to give a more comprehensive picture of her. Sather also does not use her correspondence with the Austrian Arthur Schnitzler. He was a colleague of Sigmund Freud and wrote the short story on which Stanley Kubrick’s film Eyes Wide Shut is based. As far as I know, the messages show that she was a woman with a sexy sensuality.

A MUST READ!

Despite the flimsy source base, Sather does not think about the reasons why the meeting with Ibsen is “fatal”, while we know very little about her other life experiences.

Thus Sather failed to extricate Bardash and the other three women from Ibsen’s shadow.

“Infuriatingly humble web fan. Writer. Alcohol geek. Passionate explorer. Evil problem solver. Incurable zombie expert.”