Sometimes it’s good to be reminded that everything has never been better.

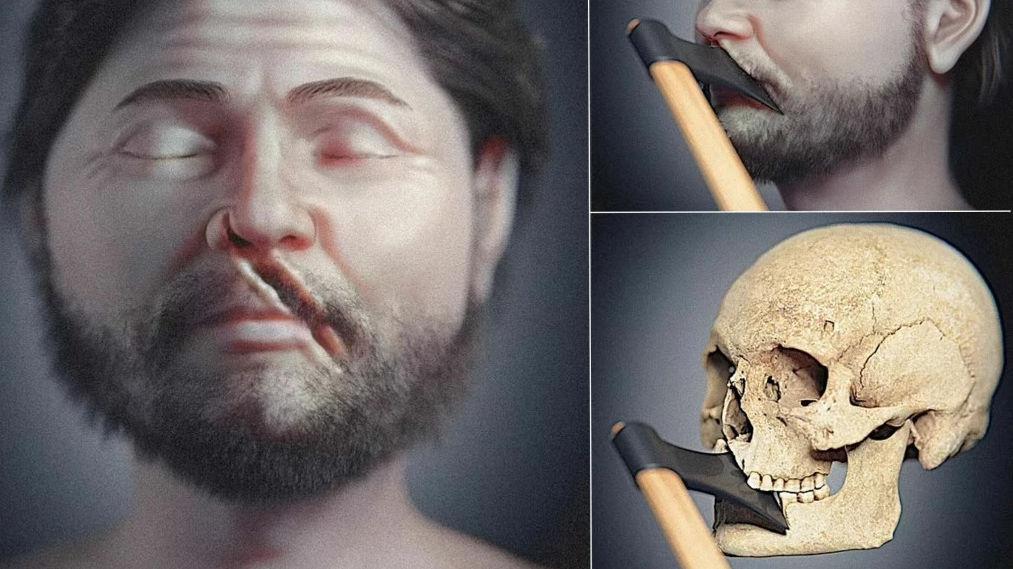

In a new study, a 3D designer has reconstructed a face from the skull of a peasant warrior.

It was found in Visby on the Swedish island of Gotland and has been dated to 1361 – the year Danish King Waldemar Atterdagh attacked the city and massacred an army of untrained and ill-equipped peasants.

And here, with 1,800 of his companions, he fell with a severe wound in the middle of his face.

– It was a massacre, says Kar Johansen, a historian and archaeologist at the medieval center in Nykoping-Falster in Denmark.

– The man here lived his whole life as a farmer and suddenly had to come face to face with Valdemar Aterdag’s seasoned and experienced knights. They had no chance, and they probably knew it, he says.

After the battle, Visby opened its gates and Waldemar Atterdagh set the city on fire.

Then Gotland continued to be part of the Danish kingdom until 1645.

According to Kari Johansen, the Swedes still hold grudges. This painting is from 1882. It shows Waldemar Atterdagh in Visby after the battle dressed in red – the color of the devil. Legend has it that the king set up three large beer vats in the square which the townspeople had to fill with treasures. ((Photo: Waldemar Atterdag Visby Fire Taxes by Carl Gustav Hellqvist, 1882) Image: Public Domain Mark 1.0

Computerized reconstruction – and guesswork

facial reconstruction, and associated studyCrucifixion, believes Nils Lenerup, professor at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Copenhagen.

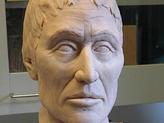

Nils Lenerup model by Sven Estridsen. The obverse is from a model of a king’s skull. Photo: Nils Lenerup/Bjorn Skrupp

He himself has worked to recreate faces from the monumental skulls – including those of Sven Estridsen, who was King of Denmark until around 1075.

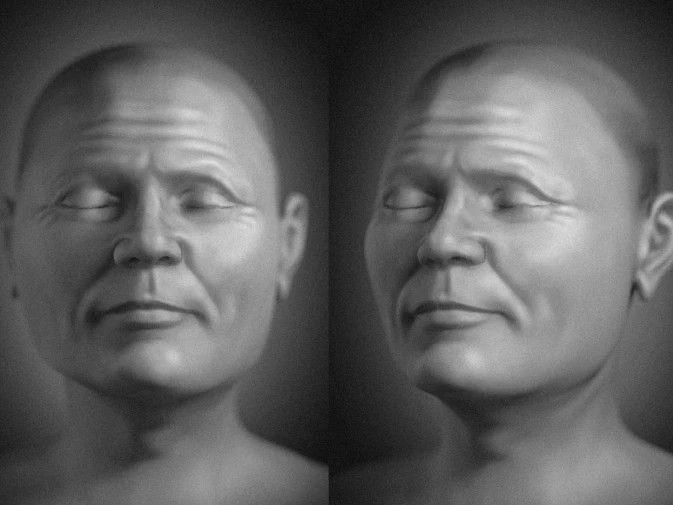

When reconstructing a face, you start with the facial skeleton and determine basic things like gender and age, he says.

– Next, one looks at anatomical studies and databases to assess the average soft tissue thickness in different places of the facial skeleton for people in this region at this time. This is how, among other things, the lips, nose or cheeks looked. Then the face is filled according to the facial skeleton in relation to the most important muscles.

And this is where the data-driven reconstruction comes in.

Reconstruction based on computer-based assessments of what a peasant warrior looked like. Photo: Cicero Moraes et al.

The rest is somewhat guesswork. Whether a person is fat or thin, has many wrinkles or a beard, blue or brown eyes, we cannot say anything about it, says Lenerup.

– They can be inspired, for example, by paintings or coins to get an impression of fashion in beards or hairstyles. But of course there is no particularly accurate evidence.

– So he didn’t like it?

– Mostly not. Niels Lehnerbe answers that it is based on conjecture, but in the study also uncertainty is explained by uncertainty.

The study does not conclude that it was the ax attack that cost the man his life, but Kåre Johannesen thinks it is entirely possible. “We don’t have the rest of his skeleton, so it could have been a spear or something else that killed him. But he likely died from the injury.” (illustration: Moraes et al.)

conveys the message

For research, these refactorings don’t contribute anything in particular. Kåre Johannesen and Niels Lynnerup agree.

But it is important to communicate.

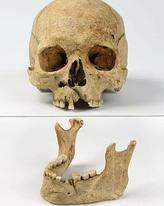

The peasant warrior’s skull, on which the reconstruction is based, was found in a mass grave outside Visby. (Photo: Gabriel Hildebrand/Historiska museet/SHM – CC BY)

— it makes the story more present to the audience, says Johansen.

– When you can see a person’s face, it is much easier to understand that the past is not a foreign gray mass of faceless people – but it was made up of real people, he adds.

Nils Lehnerb agrees:

– It shows that the Middle Ages can be horrific. And we see that he was just like you and me. He adds that one should also not forget that communication is important to research.

– Give him an iPhone and a cardigan, and he might as well be a neighbor, Johansen concludes.

– It’s trite, but also important. We can only use history for something if we understand that it is about people like us.

Reference:

Cicero Moraes and others: Facial approach to the victim of the Battle of Jutland (1361)(2022). DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.21432384

© Videnskab.dk. Translated by Lars Nygaard for forskning.no. Read the original story on videnskab.dk here . The issue was first published in Norwegian on forcing).

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”