From the Greek word for amber, electron, we get the term electricity. They discovered that when they rub amber on their fur, they can, for example, raise feathers or emit unpleasant shocks.

The Greek mathematician Thales made many observations about static electricity 600 years before our era. His conclusion was that friction with rubbing amber makes it magnetic. But different from magnetite, which was magnetic without rubbing. It will take 2,500 years before we discover the relationship between magnetism and electricity.

It is difficult to say when we learned to use electricity so early. A jar found in Baghdad in 1936 resembled a battery with a cathode and anode. The theory is that it may have been used for electroplating.

electricians

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, there was a lot of activity around the new phenomenon of electricity, and those who were interested in it called themselves electricians. They worked to create the most amazing possible displays of a phenomenon whose contours they were only guessing at.

A significant milestone in the history of electricity occurred when Newton himself became president of the English Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society. His laboratory assistant Francis Hawksby was tasked with finding amazing scientific instruments.

It was known that rubbing glass rods against wool could set off sparks, but Hauksbee went further. In 1705 he made a glass globe, which he deflated with a newly invented vacuum pump, and mounted it so that it rotated rapidly. Then the light went out and he grabbed the ball in his hand. Then the audience can see a flashing blue light inside the ball. No one understood what was happening, but in practice this was a very early type of fluorescent tube. For many years, Hauksbee machines have been the way to generate powerful static electricity.

capacitor

In the end, those who worked with electricity realized that they were working with a phenomenon that was moving. It moved in what they called conductors such as metals, the human body and other substances, but it was stopped by what they called insulators. It was all about static electricity, but they can move charge. What they couldn’t do was store energy. Until the Dutch physicist Pieter van Moschenbroek built the so-called Leiden bottle in 1745. Named after the city of Leiden, where he worked, it was a type of condenser. It quickly spread around the world, but no one understood how it works.

Removable

American revolutionary hero Benjamin Franklin was also a scientist and one of the pioneers of electricity. Hare proposed an experiment using a kite on a metal wire during a thunderstorm to conduct electricity, which he suspected was lightning, but it was never carried out. Instead, it turned out to be a long metal rod as a sort of lightning rod with a Leidner bottle at the base. Charged after collision, he formulated that positive charge flows toward negative areas. This is how we still define current, but in reality it is the negative electrons that flow towards the positive areas.

Electrical voltage

The shy and intelligent English scientist Henry Cavendish discovered hydrogen and many other things, and did a lot of research on electricity. What he is most famous for as an “electrician” is that in 1771 he used electric rods to discover the knowledge of electric potential, which he called the “degree of electricity.” Note that no sparks come from the stingray, but Ledner’s bottle did. However, the shock was much stronger than the stingrays. What he realized was that despite the higher voltage, the current was much less than a Leidner bottle.

animal electricity

In Italy, the intellectual battle between Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta in the latter half of the eighteenth century is legendary. Galvani was a physician, physicist, and biologist, famous for moving the legs of a dead frog when he struck it. This led him to launch the theory of “animal electricity” as a separate form of electrical energy. It eventually caused Volta to distance himself from the theory. He believed that there was only one type of electricity. He himself became famous when he managed to build the world’s first battery, the voltaic column, by stacking discs of copper and zinc separated by cloth dipped in salt water or sulfuric acid that served as the electrolyte.

Not only did this work, but the battery also gave off power over a long period of time. It was quite new, and it also meant that Volt is one of the basic terms in electricity.

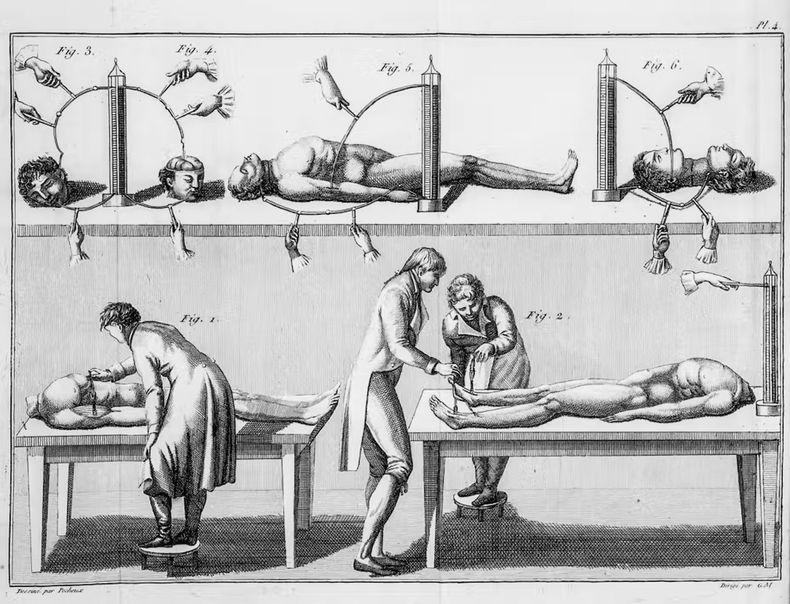

Frankenstein

The idea of animal electricity didn’t completely die with Volta. Galvani’s nephew performed a gruesome experiment on a recently beheaded criminal in London in 1803. Via two electrodes, he caused the corpse to sit by tensing its muscles. Some thought it would be possible to revive the dead with electricity, and this was Mary Shelley’s background for writing the novel. Frankenstein in 1818.

Giant battery

In excitement over Volta’s new battery, Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution in London in 1809 built a gigantic battery in the basement of the building. A total of 800 voltaic poles were erected over an area of 8 by 18 metres. He would hardly have allowed it today. He used them in a spectacular display of electric light by holding two connected coal rods close together, so that an arc occurred. This was the first time such a powerful electric light had been shown.

Many earlier “electricians”, such as Cavendish, Humphrey and others, used their knowledge to discover new elements through electrolysis, thus laying the foundation for chemistry.

electric motor

Michael Faraday was the son of a blacksmith and a cultured bookbinder, but with a keen interest in science he was a very important person in the development of electricity. It was discovered by Sir Humphrey Davy, who hired Faraday as his scientific assistant in 1812.

Faraday had little education and could read and write, but his mathematical skills were absent. Despite such a feat as building the first electric motor, his descriptions were completely devoid of equations and other mathematics. His invention was inspired by Danes Hans Christian Oersted, who discovered the magnetic field around a current-carrying electrical conductor, and Frenchman Andre-Marie Ampère, who showed that the magnetic field lies like a cylinder around a conductor.

In 1820 he showed for the first time how electric current could be converted into mechanical energy, and was behind a number of discoveries in the years that followed.

The names of these three devices are immortalized as electromagnetic devices. Farad is the unit of electrical capacitance, Ørsted is the unit of magnetic field strength (it is also a Tesla), and the ampere is the unit of current.

electromagnet

Faraday’s discoveries led to the development of the electromagnet, which in turn led to the development of the telegraph in 1837. When combined with Samuel F. B. Morse’s Morse code, it became the first widespread application of electricity. Only 18 years later, Televerket was founded in Norway. This means that Telenor has a history of 168 years. Just one year less than the history of Teknisk Ukeblad.

The article was first published in TU Magazine, Issue 1/2023

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”