This discussion expresses the views of the author. Debate entries can be sent to nettdesk@tu.no

Think of infection control as a kind of airbag. Imagine two cars, one with an airbag and one without. Which one do you want to buy?

We can expect that in a few weeks the new diseases that have spread around the world, as SARS-CoV-2 has so impressively demonstrated, will have long-term effects on our cities. But also in building construction and public transportation.

How do we make public places contagious? What can and should universities do to equip future engineers with the necessary knowledge?

A look back shows the impact of the cholera epidemic on urban development in Oslo. With more than 1,500 deaths, the epidemic in 1853 exposed the shortcomings of Oslo’s health and housing systems. As a result, standards for water supply and sewage systems were developed, as well as hygiene requirements for food production.

New regulations to improve lighting and ventilation as a result of cholera have led to entirely new building patterns. At the eastern end of the Torchov district of Oslo, workers’ housing is built with lights in the apartments, a large backyard, wide streets and access to gardens. The plans were based on knowing how disease spreads when we are too close to each other and how health and quality of life are undermined by poor housing.

Need to build a better bathroom

Unfortunately, the current COVID-19 pandemic is not the last of its kind. This raises the important question: How can we design buildings, ships and other means of transportation to reduce the spread of infection?

How do you design public spaces and use innovative technologies with people at the forefront? How do we protect their health and well-being, while improving the user experience and providing the best possible protection against diseases like COVID-19 or the flu?

Let’s first talk about the bathrooms. We need to build them better. Toilet molds must be ventilated (either naturally or mechanically) to prevent transmission of pathogens through the air. And it’s a small, relatively inexpensive design feature that nearly all public restrooms lack: toilet covers.

Flexibility of building design is a must in today’s public spaces. Conference rooms may need to be offices, and restaurant lobbies may need to become the primary dining area. Some buildings may change to function completely, as we’ve seen during the pandemic, and rooms need to be designed to be as adaptable as possible. The key word is building a sustainable public space.

At the same time, we must realize that it is impossible to completely eliminate the risk of spreading disease in public places, but it is possible to build our rooms in ways that reduce the risk. Building our common rooms with public health in mind can reduce the potential for infection. Providing safe spaces is important for engineers of all disciplines – mechanical, electrical, plumbing, lighting, acoustic, structural, civil, facade design, and vertical transportation.

The prevention and control of infectious diseases is also a race against time. Scientifically, we know more and more about diseases, but this knowledge alone is not enough. We must be able to transfer science to applied solutions. Here, engineers are in a unique position to make society more resistant to new rather than old diseases.

The speed of change is increasing

The role of buildings in public health has received relatively little attention in recent years. Its role in energy emissions and climate has dominated the focus on infrastructure, although high-level reports and European guidelines on indoor air quality have led to increased awareness even before Covid-19.

Infection control is part of creating a good environment that can and should be arranged in buildings and transportation, including how rooms are ventilated, vehicles used in public transportation and how people move into and through rooms.

Architects and engineers need to secure new projects for the future – and update existing ones – with flexible design strategies that help protect against COVID-19 and other diseases. Some of the design strategies that can be implemented will focus on indoor air quality. It includes redesigning the heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.

The new systems can support the control of airborne pathogenic microorganisms by improving filtration and avoiding central recycling as much as possible. Improving ventilation is another area that will receive attention.

New rooms can be built with more efficient windows to allow more outside air to flow in, or with improved mechanical or mixed ventilation systems. Since every surface, button, or knob can be a potential source of illness, engineers can use sensors and sound-activated technology to make buildings as untouchable as possible — from ringing an elevator and turning on the lights to flushing the toilet.

Skills, knowledge and ability

Skill barriers include the need to ensure that those responsible for public spaces know what good infection control looks like. They must have a well-thought-out approach to managing infection risks and motivate and act accordingly, and they must know when they need additional technical support and where to find it.

In Norway, there is a lack of specialized training in health-related subjects in the architecture and engineering education curricula, both at the basic and further education level. This leads to a low level of awareness and poor technical competence in dealing with various health related issues.

Even in sectors like healthcare, which have clear regulations and a clear mandate to manage health and safety for vulnerable populations, skill levels and competencies vary. This comes with varying levels of organizational maturity across operators and sectors, as well as the ability and motivation of owners to understand, manage and manage infection control issues.

The government should provide support for mapping knowledge and skills requirements across the construction industry, public institutions, the transportation sector and the engineering professions to manage buildings in a way that minimizes the risk of infection.

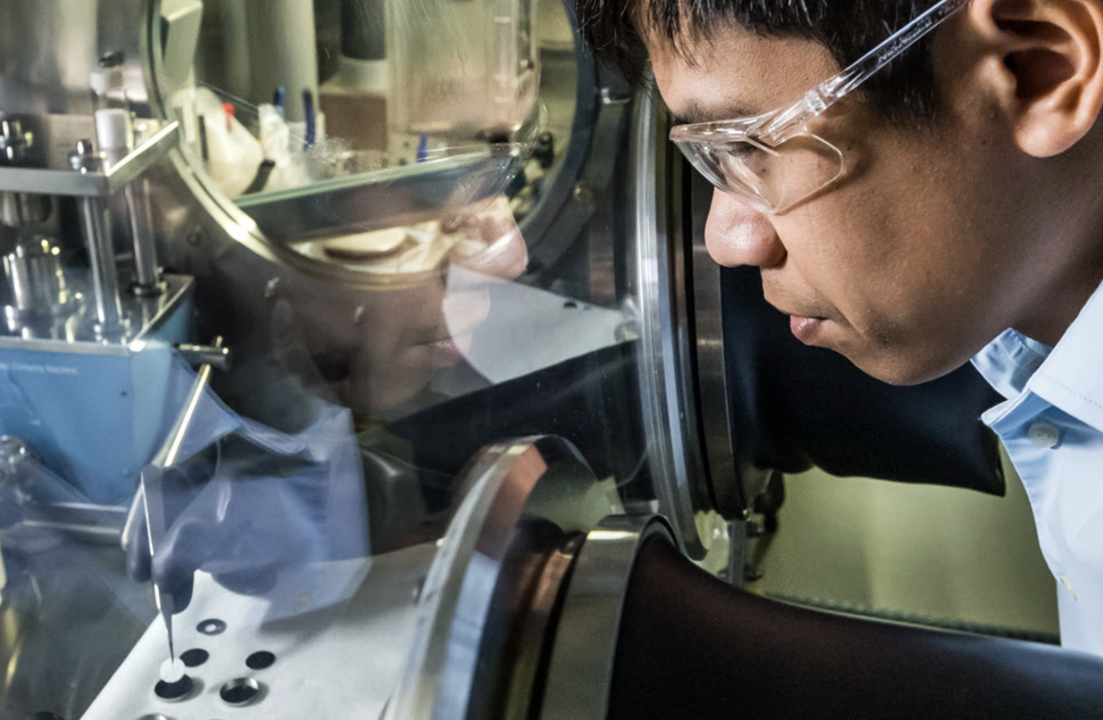

The University of Southeast Norway is training experts in infection control and recently received funding for a major European project. The research project will provide a basis for making the shipping industry epidemic-resistant. At the same time, we will be able to transfer the results to buildings and offices, as well as transportation and other sectors, thereby gaining research-based knowledge about technical infection control. In order to bring education to the space of the future, we need support from public authorities and industry.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”