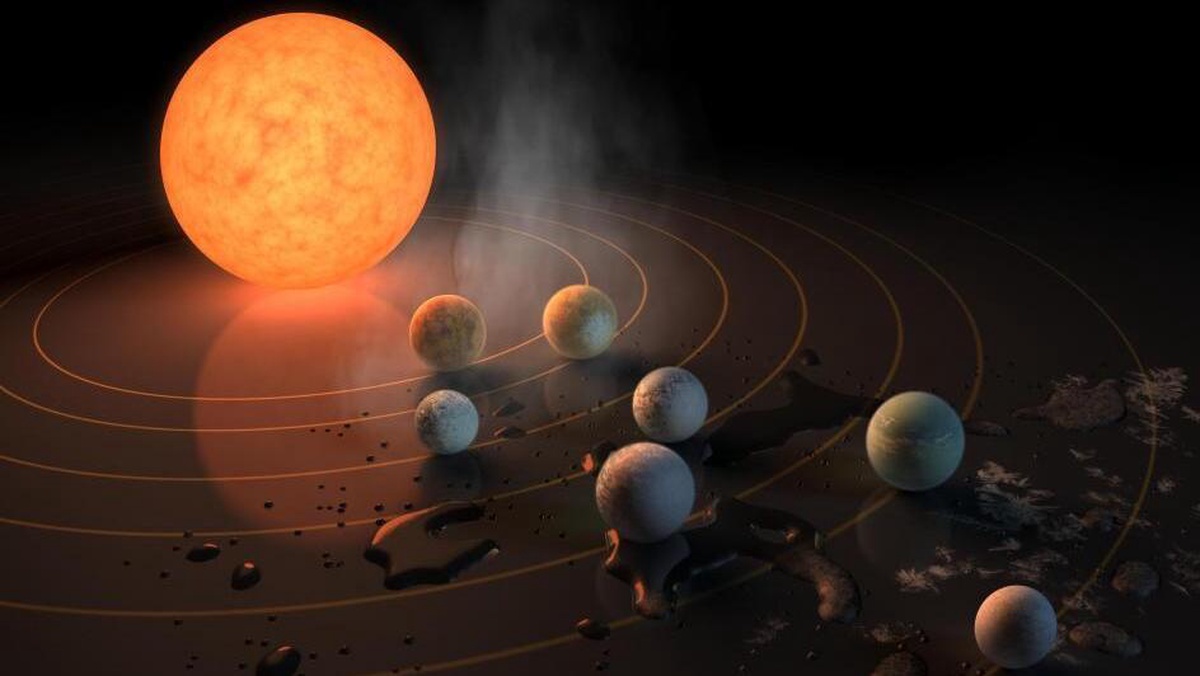

The number of exoplanets, planets orbiting stars other than our sun, has exceeded 5,000. There are several thousand more candidates on the waiting list.

– We have to limit this number, says Professor Trond Torsvik in the Department of Earth Sciences.

Few of the thousands of exoplanets are interesting candidates when searching for life elsewhere in the universe. It is precisely this narrowing down of the goal of the Center for Habitability of Planets (PHAB), which the Research Council recently awarded status as a Center of Excellence for Research.

“I hope we can learn what’s really important for habitability,” says Professor Stephanie Werner in the Department of Earth Sciences.

outer planets

An exoplanet, also known as an exoplanet, is a planet orbiting a star other than our sun. The first exoplanet of a star of the same type as the Sun was discovered in 1995 around the star 51 Pegasi. (source: The great Norwegian encyclopedia)

At the time of writing, NASA has registered 5,178 exoplanets on its website Exploring the outer planets. 8,933 planets were registered as “candidates”.

Torsvik and Werner will lead the new center and now have ten years to establish new buildings in the search for life in space.

We are geologists and geophysicists. It’s not about what the origin of life is, it’s about the geologic conditions and temperature fundamental to life’s development, Torsvik tells Titan.uio.no.

Starting from the soil

The researchers turned their eyes outward toward infinity, but their feet were firmly planted on the ground. on planet earth. Because we know life evolved here, but also because we still have a lot to learn about our planet.

We want to know if we understand Earth well enough to be able to say something about other planets and about their habitability requirements, says Werner.

They have a good starting point. The new research project stems from Earth Development Center and its dynamics (Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics, CEED), which is also a center of research excellence and is in the process of closing.

– At CEED, we’ve worked with the last 500-600 million years. One of the first things we want to do now is try to build the history of the Earth again. “We start with how our planetary system formed,” Torsvik says.

The Earth has not made it easy for scientists to map the first blocks of its 4.5 billion-year history.

Early history was destroyed by plate tectonics. To understand the first billion years on Earth, we need to look at the other planets in our solar system. Tursvik says history is preserved there.

Mars tells us a lot about our history

Even if we don’t find life on Mars or Venus, it is useful to study it. We can learn something from what happened to them and therefore our planet. That’s why Werner and Torsvik are keeping a close eye on what’s happening right now with rovers on Mars.

Some say you should go to Mars to study the early Earth. Werner says it’s important to study water and mineralogy on Mars because we can compare with what we know about Earth.

– Observations on Mars now may not be the most important to us, but they will be very exciting when persistence sends samples back to Earth in a few years, she says.

The land was also uninhabitable

Neither Tursvik nor Werner believe that life will be discovered on other planets in our solar system. But Mars and Venus can say a lot about how the planets evolved, where they came from and where they’re heading.

The land was also uninhabitable. Today’s situation, Torsvik points out, is just a snapshot.

Once the land was uninhabitable. It will again become uninhabitable. This means that scientists are not only looking for planets where conditions are right for life at the moment. A planet can be habitable in some periods of time and uninhabitable in others.

We want to find out what are the most important factors to call a habitable planet, but also on what time scales. In periods, one parameter may be more important than another, but on shorter time scales they can be very different, says Werner.

Astronomers need geologists

In recent months, the whole world has been fascinated by the first results from the new James Webb Telescope. Stephanie Werner is also involved in telescopes planned by the European Space Agency, among which are Plato and Ariel.

James Webb can do the studies we need. It’s not as detailed and repetitive as the European Space Agency’s space missions, Plato and Ariel, but it will be exciting. We hope there will be plenty of information that can eventually test our models, says Werner.

Astronomers naturally bear the main responsibility for telescopes, but they need professionals with other knowledge to interpret what they see.

To understand how an Earth-like planet evolved, we need geologists. Astronomers get the information and the data, and geologists discover the model that we assume best explains what they’re observing, Werner says.

Astronomers are good at finding these objects, but they need a geologist to explain what these things mean. Tursvik says they need expertise from our planet.

The same goes for the other method. Therefore, PHAB will ensure that astronomers are represented in the research group.

The first life is stored as a stone

Evolutionary biology will also be represented. After all, it is about life.

It’s mostly about younger things, Tursvik says, like how life flourished and mass extinctions.

They should not directly address the big question of what the first life was on Earth – where and how the first life arose.

There is a great debate about what is the ideal environment for life. The most important thing for us, Torsvik says, is to know what the environment was actually like at the time.

Geologists often discover the first life.

There are 3.5 billion years old rocks that are clearly formed by bacteria. Blue-green algae, as we call them, make up very special rocks. They are not concrete fossils, but sediments with layers of dead organisms. They are called Stratolites, Torsvik says.

Biology can also say something about what you can look for in the atmospheres of exoplanets. It’s not that telescopes see exactly what’s going on on their surfaces.

– What were we? Can Observation on other planets, is the chemistry of the atmosphere. Werner says biology will be able to identify the processes that could influence this chemistry.

By studying the atmosphere, you can tell something about what happened under it, under this planet.

No plans to move

Habitable in an interplanetary context does not mean that we as humans should be able to live there. Werner and Torsvik are not looking for a place to move to if it becomes impossible to live on Earth. They also leave speculation about life in space and how it might turn out to be others.

The probability is zero and nothing to find a planet with a civilization like ours, but maybe we can see a planet on its way to becoming one, says Torsvik.

Of all the exoplanets out there, they hope to be able to circle a few better candidates than the vast majority are lifeless.

The goal is to predict, based on our knowledge of Earth and the other planets in our solar system, what observations we need to make sure we don’t just imagine. Werner says that in ten years we can point to a planet and say it has a planetary evolution that makes it very likely that life could exist there.

– Find out whether there really is life or not, of course we can’t say that.

The article was first published in Titan.uio.no

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mentormedier/5VQQLGKGCVA2TC3KURKTRX4OMA.jpg)