The government’s new self-produced renewable electricity sharing scheme, which comes into effect on October 1, is a step towards sharing electricity locally. The new sharing system allows electricity customers in housing associations, multi-family dwellings and commercial buildings to share the electricity they produce themselves, for example from solar cells. By doing so, they avoid grid rent and consumption charges for this electricity.

Researchers at Sintef and NTNU have now taken a closer look at the pricing models that will work best when this solar power comes to market.

Although we don’t have any local energy communities in Norway yet, this is something that will also come to this country, according to the researchers.

Power sharing in local energy communities

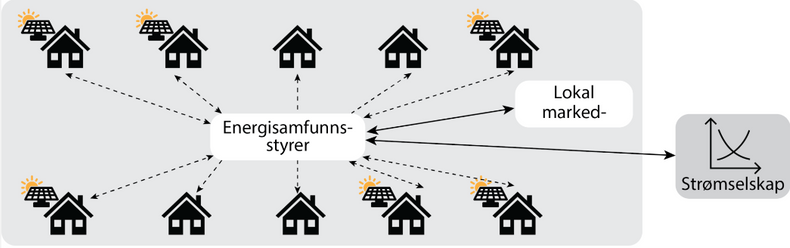

Local energy associations are separate legal entities that produce, distribute and consume electricity. Here, some members of the energy community can produce a lot of energy, others somewhat less, while others are only consumers.

Within these local energy communities, the price of locally produced electricity must be well set. In addition to those who produce and consume electricity, distribution network companies, innovative electricity companies and authorities must also be involved, says Sigurd Bjarjov, a researcher at Sintef Energi.

Since the choice of price mechanism largely determines the price, there are many questions related to this choice. How should the benefits of domestic trade be distributed between producers and consumers? Should producers, who ultimately invest in renewable energy, get most of the savings, or should consumers get a larger share of the pie?

If we see energy communities in Norway in the future, these questions will be important for those who manage local energy communities. Authorities must also carefully consider the long-term incentives they offer through the participation system, so that actors have predictability.

– If the authorities maintain the principle of exempting local electricity sharing from taxes and network rent, we know that the seller will get a higher price by selling locally than he will get by selling electricity to the network company. At the same time, the buyer will pay less. This gives a lower and upper bound on the price that can be negotiated within the local energy community, Bjargov says.

How to choose a price model?

How electricity prices are set becomes an important design choice for the local energy community because it has a direct impact on how profitable it is to invest in solar panels.

The pricing model, and the data that needs to be shared, are key questions that require answers for domestic energy trading to take place, says research fellow Marthe Fogstad Ding at NTNU’s Department of Electric Power.

In the Recent study Ding, Bjargov and their colleagues looked closely at three different pricing models and how they affect the price of electricity for a local energy community.

The research was conducted in a case study of a fictitious market within a fictitious local energy community comprising ten units producing different fractions of solar energy. Some units in the model do not produce energy, but only buyers.

-Based on our findings, we recommend local energy communities start with a price model we call “supply and demand,” simply because it’s an easy place to start. In the long term, we believe a price model based on balanced pricing will be the current model, but then privacy-related challenges will need to be better addressed, says Ding.

Best for consumers

Supply and demand system It finds the relationship between supply and demand and uses it to determine the price between the lower and upper limits. This is determined by prices on the national market as well as discounted online fees, taxes and rent. If there is a large surplus of solar energy, the price will be very close to or equal to the minimum. If there is little solar production and high demand, the price will be set near the upper limit.

– This arrangement is simple and understandable and requires very little data exchange. One advantage is that it is open and easy to explain to the general population. At the same time, it is the price model of the three models that mainly benefits consumers rather than producers, Deng says.

Fair pricing model

Balance method It should, according to economic theory, be the fairest. Here the price is determined assuming perfect competition in the local market. The average local market price falls between the other two methods. This makes it an acceptable compromise for both buyers and sellers. The method is both simple and open as the price is set at either the upper or lower limit depending on whether there is more demand or supply. This is a familiar concept to many.

However, data security is not good in this pricing model because it requires a lot of data from all market participants. Bjargov says these challenges can be solved, but may pose a problem for privacy-conscious consumers.

Latest models, based on Distributed optimizationis not a pricing model recommended by researchers, although it does not require sharing detailed data.

-It is more complex and difficult for most people to understand. It’s also not open, and it offers local prices that are higher on average than the other two pricing models, Ding says.

Now the researchers want to try different price mechanisms in a pilot project to verify the methods they used.

– Such a test will also be able to provide us with useful inputs regarding participants’ experiences and how they experience data sharing and openness of methods,” Bjargov says.

The article was first published on Gemini.No

“Web specialist. Lifelong zombie maven. Coffee ninja. Hipster-friendly analyst.”